A horrible, wonderful, important book

Pigs prematurely taken from their mothers root incessantly for something to chew or suck on; and if they are pigs spending their abbreviated lives in a factory farm, where maybe 500 animals are crowded into a space no bigger than a living room, the thing they try to chew on is the tail of the hog in front of them. This is not a happy habit for the industrial farmer: chewed tails can result in infections, and pigs that die, in Matthew Scully’s pitch-perfect phrase, ”an unauthorized death.”

The factory farmer’s solution? When the piglets are weaned, a good 12 to 16 weeks before nature had planned, their tails are docked, the lower part amputated with a pliers-like instrument. That small operation leaves the pigs with hypersensitive tails, which means the animals will not get complaisant and will struggle ever after to keep their clipped, throbbing appendages out of the mouths of their penmates.

Should you be inclined to pity the beasts for that or any other detail of their treatment in today’s giant meat-making plants, however, the executives in charge of booming factory farms like Smithfield Foods in Virginia, which kills 82,300 pigs a day — a quarter of the nation’s total — are eager to set your conscience at ease. When Scully asked Sonny Faison, head of Smithfield’s Carroll’s Foods division, in North Carolina, whether there isn’t something ”just a little sad” about confining millions of animals to cramped concrete enclosures, where there is no sun, wind, rain or even so much as a scattering of straw to sleep on, Faison declared au contraire. ”They love it,” he insisted. ”They’re in state-of-the art confinement facilities. The conditions that we keep these animals in are much more humane than when they were out in the field.” Another Smithfield supervisor seconded the notion, painting a bleak picture of the life of free-ranging swine: ”I mean, you put ’em out, they kind of scrounge around in the mud, and in the summer, around here, animals that are outside risk getting mosquito bites and things.”

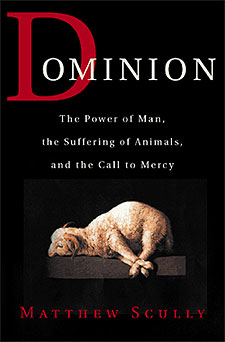

Dominion is a horrible, wonderful, important book. It is horrible in its subject, a half-reportorial, half-philosophical examination of some of the most repugnant things that human beings do to animals, notably keeping them in the factory farms that have taken over the business of supplying America’s insatiable meat tooth; and hunting them down on a new style of ”safaris,” which are nothing more than canned, risk-free opportunities to bag exotic species as easily as one might drown a suckling kitten. The book is wonderful in its eloquent, mordant clarity, and its hilarious fillets of sanctimonious cant and hypocrisy. For example, Scully quotes from a book called In Defense of Hunting, by James A. Swan — an authority favored by Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf and other proud, manly-men hunters — citing a passage that addresses the critics who weep over the animals and asks, aren’t they special, even sacred, too?

Dominion is a horrible, wonderful, important book. It is horrible in its subject, a half-reportorial, half-philosophical examination of some of the most repugnant things that human beings do to animals, notably keeping them in the factory farms that have taken over the business of supplying America’s insatiable meat tooth; and hunting them down on a new style of ”safaris,” which are nothing more than canned, risk-free opportunities to bag exotic species as easily as one might drown a suckling kitten. The book is wonderful in its eloquent, mordant clarity, and its hilarious fillets of sanctimonious cant and hypocrisy. For example, Scully quotes from a book called In Defense of Hunting, by James A. Swan — an authority favored by Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf and other proud, manly-men hunters — citing a passage that addresses the critics who weep over the animals and asks, aren’t they special, even sacred, too?

”A thing can become truly sacred only if a person knows in his or her heart that the object or creature can somehow serve as a conduit to a realm of existence that transcends the temporal,” Swan argues. ”If hunting can be a path to spirit, unhindered by guilt, then nature has a way of making sure that hunters feel compassion.”

Dominion is important in large measure because the author, an avowed conservative Republican and former speechwriter for President George W. Bush, is an unexpected defender of animals against the depredations of profit-driven corporations, swaggering, gun-loving hunters, proponents of renewed ”harvesting” of whales and elephants and others who insist that all of nature is humanity’s romper room, to play with, rearrange and plunder at will.

As his friend and fellow political commentator, Joseph Sobran, said on hearing of Scully’s dietary preferences: ”A conservative, with a Catholic upbringing, and a vegetarian? Boy, talk about aggrieved minorities!” At the very least, Dominion will encourage patronage of the small, independent organic farms, where the cattle are grass-fed and treated humanely, an option that Scully calls ”a decent compromise.”

Scully’s argument is, fundamentally, wholly a moral one. It is wrong to be cruel to animals, he says, and when our cruelty expands and mutates to the point where we no longer recognize the animals in a factory farm as living creatures capable of feeling pain and fear, or when we insist on an inalienable right to stalk and slaughter intelligent, magnificent creatures like elephants or polar bears for the sheer, bracing thrill of it, then we debase ourselves. As the earth’s most powerful species and the only one capable of meditating on our actions, we have a moral responsibility to treat the animals in our care with kindness, empathy and thoughtfulness, Scully says. When we forfeit that responsibility, we forfeit the right to any of the little self-congratulatory designations we have claimed: as God’s ”chosen” ones.

As Scully sees it, we may be ”of” nature but we are not in it. For better or worse, we have dominion over the earth, and how we manage that position, whether as bloodthirsty tyrants or as benign patrons, is a core measure of our worth. ”Animals are more than ever a test of our character, of mankind’s capacity for empathy and for decent, honorable conduct and faithful stewardship,” he writes.

The author takes a particular dislike toward those who argue that animals, being incapable of dwelling on their mortality, therefore don’t really suffer the way neuronally well-endowed humans can suffer. He also finds fault with those he considers moral relativists, like the philosopher Peter Singer, who has argued that reason, rather than knee-jerk compassion or squeamishness, should dictate what we deem the comparative worth of the lives of animals or severely handicapped infants. Scully can wax self-righteous and absolutist, and he considers the ”squeamishness factor” to be a handy indicator of something, like a factory farm, that is morally wrong. ”It is usually a sign of crimes against nature that we cannot bear to see them at all, that we recoil and hide our eyes,” he writes, ”and no one has ever cringed at the sight of a soybean factory.”

Overall, a beautiful and thoughtful book that forces some of us to look more closely into the mirror.

~~ Excerpted from The New York Times Book Review, by Natalie Angier

Matthew Scully, interviewed by National Review Online:

National Review Online: In a nutshell, how are we abusing dominion, our stewardship over animals?

Matthew Scully: In the same way that human beings are prone to abusing any other kind of power — by forgetting that we are not the final authority. The people who run our industrial livestock farms, for example, have lost all regard for animals as such, as beings with needs, natures, and a humble dignity of their own. They treat these creatures like machines and “production units” of man’s own making, instead of as living creatures made by God. And you will find a similar arrogance in every other kind of cruelty as well.

Washington Post Viewpoint: Animal Cruelty and the Need for Reform

Sad to say, but Scully is a phony. It’s doubtful he believes anything he wrote in the book. He wrote the RNC speech for hunter extraordinare Palin. Read this for a beginning:

http://www.statesman.com/blogs/content/shared-blogs/washington/washington/entries/2008/09/03/palins_speechwr.html

If memory serves Scully was also writing speeches for the prez when the prez was selling the USA on a war with Iraq because of supposed

WMD. A real prince of a guy.

to Mitch: Scully isn’t a single issue guy. You would prefer he were writing speeches for President Horse Slaughter?

To the author: Compassion IS and will ALWAYS be a Conservative virtue. The title, “A Compassionate Conservative” implies that this is something unusual. Admittedly most vegans are probably liberal, but i mind that most are also inconsistent in their compassion, even if well-meaning.

This book was powerful and amazingly insightful. An individual would not spend this intense energy on writing such a culturally controversial topic, which in the end benifits the animals and go against the belief of the majority, if he did not fully support and believe in the words. Even if he chooses to write for Palin, who i am not supportive of, and shares another set of world beliefs…. there is enough reason and morral value in him to also belive whole heartly in this.

A very intelligent discussion — Now will the Catholic church and its leader, the Pope, please address this issue? Does this church realize that many people have left it because the Church completely neglects issues of compassionate treatment of animals, not to mention downright sadist cruelty.

Perhaps the neglect is not complete, but care for our companions in creation is far from adequate.

My earlier message was perhaps sent in haste. I’ve only read an excerpt from Matthew Scully’s book, but plan to buy the book. Does anyone know if the Catholic Church has taken a position on the treatment of animals? This would seem to fall under the morality category, and a compassionate position would help end the terrible suffering of animals.

Eileen

Eileen,

I was looking for a review of “Dominion” when I saw your post. Highly recommend Matthew Scully’s book. He is Roman Catholic. Think this best sums up the Churches position on this subject.

“In an interview, Pope Benedict XVI, then known as Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, was asked by German journalist Peter Seewald about his views on animal welfare (Pope Benedict XVI. God and the world: a conversation with Peter Seewald. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2002; 78). The future Pope responded with empathy, calling animals our “companions in creation.” He went on to advise that,

we cannot just do whatever we want with them. … Certainly, a sort of industrial use of creatures, so that geese are fed in such a way as to produce as large a liver as possible, or hens live so packed together that they become just caricatures of birds, this degrading of living creatures to a commodity seems to me in fact to contradict the relationship of mutuality that comes across in the Bible.

There is some recognition in Europe that we need to rethink our categorization of animals as property or not-property. The category of “sentient beings” is starting to be talked about, and has even made its way into the Swiss constitution. The fact that we are seeing animal welfare lawyers and changes to law curricula is positive.

Good grief! Another bleeding heart whose sensitive soul is one with our porcine friends. If only meat could arrive — in quantity — in our supermarkets without those messy intervening steps. It appears the era of cheap food may be coming to an end. Ethical quibbling about sources of food may be the first casualty when people get hungry. Really hungry.

I read Scully’s book a number of years ago. It was impacting to say the least. Scully made this point very pointedly: “The people who run our industrial livestock farms, for example, have lost all regard for animals as such, as beings with needs, natures, and a humble dignity of their own. They treat these creatures like machines and “production units” of man’s own making, instead of as living creatures made by God. And you will find a similar arrogance in every other kind of cruelty as well.” We have turned a blind eye to things and are so accustomed to how things are that we fail to understand the impact, animals are not commodities but living, breathing creatures created by He Who Created All Things. Native Americans respect the Earth and all those who inhabited the planet. As Chief Seattle stated: “Humankind has not woven the web of life. We are but one thread within it. Whatever we do to the web, we do to ourselves. All things are bound together. All things connect.” All things are connected. What we do to the animals we do to ourselves. The white man (for the most part) only sees the machine and the cogs that fit into place that make it run. The machine is of his own creation to simply his world. But in the process, he has narrowed his focus and does not see the whole picture, the whole planet and those other creature who live here and share it with him. Yes, I do think the Machine, which is man’s own creation, has now consumed him. We are so focused on the gadgets of life that we really fail to view the wonders of life itself. Around us is a great big planet filled with everything that the Creator of All Things has wanted to bless us with. Yet, we do not see it. We ignore it! We are simply caught up in our short-sightedness and infatuation with our own creation – The Machine. It’s really sad, but we have become slaves to the Machine and now it’s our task master, ruling our lives and consuming our thoughts. Can we break free? Perhaps not. We are now become the Borg. We are part of the Machine. And just like The Terminator, the Machine might decide it’s time to eradicate us from the planet. Sometimes life is stranger than fiction, but sometimes fiction is prophetical of life. We are warned so many times, over and over again. Yet we choose to not listen. Is it too late?

I WANT SO BADLY FOR THIS BOOK TO BE MANDATORY READING BY ALL CHILDREN, WHETHER JR. HIGH OR HIGH SCHOOL ——–THERE IS THE POTENTIAL TO TURN SO MANY PEOPLE AROUND.