Flock & Fable: Animals and Identity in Contemporary Art, curated by Amie Robinson, runs at New York’s Chelsea Art Museum to July 31.

The exhibit presents the works of eleven artists who use animal imagery to investigate forms of identity: racial, sexual, spiritual, social, political, psychological, and moral. In identifying with the animal, the artists create modern day fables. Traditionally, fables seek to instruct, to inform and bestow on their audience a “moral maxim, social duty, or political truth.” They aim at the improvement of human conduct, at revealing personal and social identities, and do so by concealing their agenda in the guise of fictitious characters—animals.

Racial and sexual identities and stereotypes are conveyed in the work of Kara Walker and Marc Swanson. Kara Walker’s provocative silhouettes confront our perceptions of identity in terms of history, culture, gender and race. The wall painting Pastoral portrays the metaphorical “black sheep” as an ambiguous hybrid being that is “part human, part animal, part black and part white.” It exposes stereotypes of ethnic identity, revealing colonialist myths depicting the sexuality of black women as animalistic. Sexual identity is also explored through personal iconography in the work of Marc Swanson. Covering two stag heads—a symbol of maleness—in rhinestones, he confronts coming to terms with his own homosexuality and his politically conservative background.

Racial and sexual identities and stereotypes are conveyed in the work of Kara Walker and Marc Swanson. Kara Walker’s provocative silhouettes confront our perceptions of identity in terms of history, culture, gender and race. The wall painting Pastoral portrays the metaphorical “black sheep” as an ambiguous hybrid being that is “part human, part animal, part black and part white.” It exposes stereotypes of ethnic identity, revealing colonialist myths depicting the sexuality of black women as animalistic. Sexual identity is also explored through personal iconography in the work of Marc Swanson. Covering two stag heads—a symbol of maleness—in rhinestones, he confronts coming to terms with his own homosexuality and his politically conservative background.

Religious and spiritual identity is explored in the work of several artists, including Patricia Bellan-Gillen, Graciela Iturbide and Kimowan Mclain. Patricia Bellan-Gillen appropriates animal symbols and icons from various religions. Ideas from doctrine, faith and myth fuel the work and she invites the viewer to instinctually find their own autobiographies in her paintings. The haunting images of Graciela Iturbide portray Mexican cemeteries swarmed by locusts and somber skies with flocks of birds as mythical human spirits: “I testify the poetic dimension of men and magic, and I see a kind of mystic of the every day life.” Filling thin, swaying paper walls with images of moths, biblical metaphors for the ephemeral, Kimowan Mclain’s work reminds us that our existence is temporary. He writes, “I know people like moths. They are not imbalanced by an overly zealous devotion to light, but are equally weighted by the substance of dark. Shall we brush these people aside as if they were dry, brittle wings? Or clean away their dark histories and mournful days?”

Religious and spiritual identity is explored in the work of several artists, including Patricia Bellan-Gillen, Graciela Iturbide and Kimowan Mclain. Patricia Bellan-Gillen appropriates animal symbols and icons from various religions. Ideas from doctrine, faith and myth fuel the work and she invites the viewer to instinctually find their own autobiographies in her paintings. The haunting images of Graciela Iturbide portray Mexican cemeteries swarmed by locusts and somber skies with flocks of birds as mythical human spirits: “I testify the poetic dimension of men and magic, and I see a kind of mystic of the every day life.” Filling thin, swaying paper walls with images of moths, biblical metaphors for the ephemeral, Kimowan Mclain’s work reminds us that our existence is temporary. He writes, “I know people like moths. They are not imbalanced by an overly zealous devotion to light, but are equally weighted by the substance of dark. Shall we brush these people aside as if they were dry, brittle wings? Or clean away their dark histories and mournful days?”

Political truths and social identity are evident in the fables of Cornelia Hesse-Honegger, Andrew Johnson, and Rosemary Laing. Cornelia Hesse-Honegger sets her tales in Chernobyl, Three Mile Island and in the shadows of international nuclear power plants and her cast of characters is unfortunately not fictional; it is rather exquisitely illustrated insects suffering numerous mutations from the effects of radiation in their environment. The frog in The Closed Mouth, a large oil painting by artist Andrew Johnson, is far from becoming a fairy tale prince. This enormously bloated creature, isolated in darkness, is an allegory of consumption and a metaphor for America’s foreign policy. The photographs of Rosemary Laing also portray birds in flight; yet among them floats a woman in a wedding dress high above the mountains of Australia. They stir in us our desire to become animal, to fly: “Flight sits in our consciousness as a kind of fantasy or dream. It is a metaphorical notion. Children dream of flying. It is a very escapist notion to be able to fly. Super heroes fly.” Upon closer inspection however, there are bullet holes in the woman’s chest. Like Icarus, she is falling.

Political truths and social identity are evident in the fables of Cornelia Hesse-Honegger, Andrew Johnson, and Rosemary Laing. Cornelia Hesse-Honegger sets her tales in Chernobyl, Three Mile Island and in the shadows of international nuclear power plants and her cast of characters is unfortunately not fictional; it is rather exquisitely illustrated insects suffering numerous mutations from the effects of radiation in their environment. The frog in The Closed Mouth, a large oil painting by artist Andrew Johnson, is far from becoming a fairy tale prince. This enormously bloated creature, isolated in darkness, is an allegory of consumption and a metaphor for America’s foreign policy. The photographs of Rosemary Laing also portray birds in flight; yet among them floats a woman in a wedding dress high above the mountains of Australia. They stir in us our desire to become animal, to fly: “Flight sits in our consciousness as a kind of fantasy or dream. It is a metaphorical notion. Children dream of flying. It is a very escapist notion to be able to fly. Super heroes fly.” Upon closer inspection however, there are bullet holes in the woman’s chest. Like Icarus, she is falling.

Emotional and psychological identities are clear in the work of Helen Altman and Kojo Griffin. The various animals in Helen Altman’s uniquely rendered torch drawings are isolated from their flock, alone, defenseless, floating in a sea of white and consumed by nothingness. The viewer can not help to feel compassion, sympathy, and fear for the animal; and perhaps to remember a similar feeling in their own lives, thus ultimately feeling empathy. In his psychologically charged paintings, Kojo Griffin uses anthropomorphic figures, human bodies with animal heads, to convey the human condition. Placed in an ambiguous space, the characters interact and engage us in an open, and often violent or awkward narrative. He “scratches the surface of societal scabs, making do with the puss or what is often left out of the fictions: shame, impotence, cruelty, hysteria, rage, failure, hostility, anxiety, fear and the abject.”

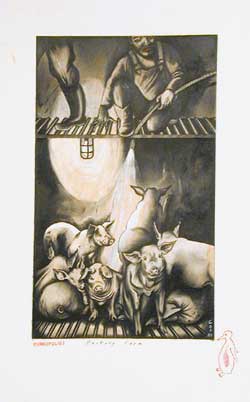

Do animals lose their identity, however, if we impose upon them our own? In his book The Postmodern Animal, Steve Baker writes that, “the representational, symbolic and rhetorical uses of the animal must be understood to carry as much conceptual weight as any idea we may have of the ‘real’ animal, and must be taken just as seriously.” Sue Coe addresses the reduction of the animal in her series Porkopolis. In sketches and drawings created in slaughterhouses (where photography is forbidden) she gives names and honors the identities of the otherwise tagged, numbered masses of the factory farm industry. Her work questions criticism that animal imagery is too sentimental, claiming that these accusations are made only to “prevent an outcry against cruelty, to silence criticism against bad science.”

Do animals lose their identity, however, if we impose upon them our own? In his book The Postmodern Animal, Steve Baker writes that, “the representational, symbolic and rhetorical uses of the animal must be understood to carry as much conceptual weight as any idea we may have of the ‘real’ animal, and must be taken just as seriously.” Sue Coe addresses the reduction of the animal in her series Porkopolis. In sketches and drawings created in slaughterhouses (where photography is forbidden) she gives names and honors the identities of the otherwise tagged, numbered masses of the factory farm industry. Her work questions criticism that animal imagery is too sentimental, claiming that these accusations are made only to “prevent an outcry against cruelty, to silence criticism against bad science.”

Images:

Kara Walker, Pastoral

Patricia Bellan-Gillen, The Speed of Your Tongue

Rosemary Laing, Bulletproofglass #4

Sue Coe, Factory Farm

From Chelsea Art Museum